The Coffin Memorial

A Tribute from the Colored People of Cincinnati

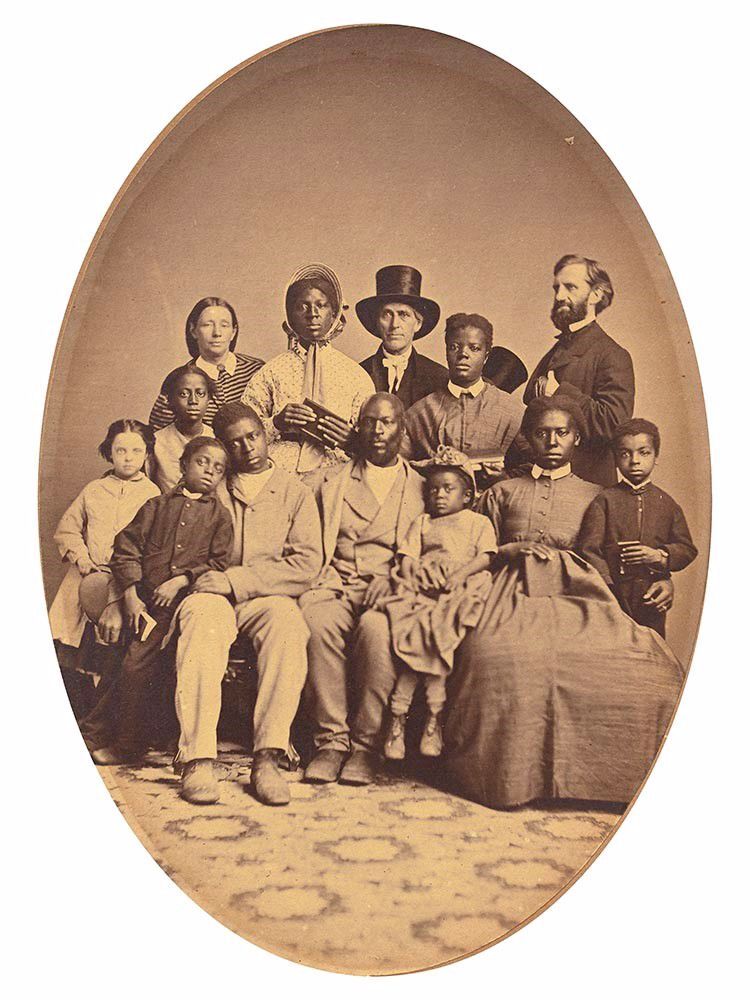

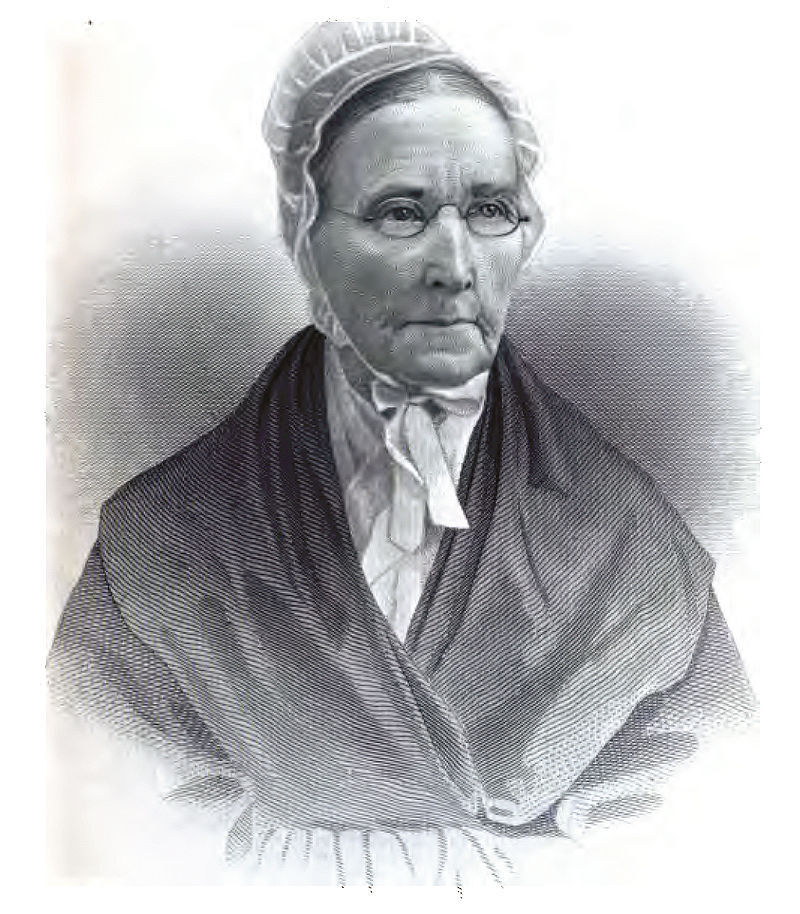

Why would dozens of African Americans raise money for a grave marker for a white couple who had died decades earlier? In 1902, leading citizens dedicated a large, granite monument to Quaker abolitionists, Levi and Catharine Coffin, in Spring Grove Cemetery, and held Memorial Day ceremonies there for years afterward.

Confederate monuments proliferated in the early 1900s soon after Southern states enacted laws to disenfranchise African Americans and segregate society. The United Daughters of the Confederacy sponsored hundreds of statues, including the common “soldier at parade rest” in Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery in Columbus, Ohio in 1902, to uphold white supremacy and reshape Civil War history.

As a counter measure, a large group of Black leaders, most of whom were religious ministers and politically active, united to honor the “President of the Underground Railroad,” Levi Coffin (1798-1877), and his wife Catharine Coffin (1803-1881) with a $500, six-foot tall granite memorial in Spring Grove Cemetery. Interest in the Coffins renewed at the turn of the century also because Charles Webber exhibited his painting, The Underground Railroad, featuring his deceased friends helping runaways, at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. Subsequently, white citizens purchased the piece for the Cincinnati Art Museum.

Quaker abolitionists, the Coffins assisted thousands of freedom seekers, both in Newport (now Fountain City), Indiana, ca. 1826-1847, and Cincinnati, 1847-1865. After the Emancipation Proclamation, Levi Coffin raised over $100,000 for the Western Freedmen’s Aid Society to help formerly enslaved people establish businesses and obtain formal education. After the society ceased operations in 1870, when the 15th Amendment granted African American men the right to vote, Coffin retired and wrote his memoir. For years, the Coffins also supervised the Colored Orphans Asylum, gratis, near their home at Van Buren and Melish.

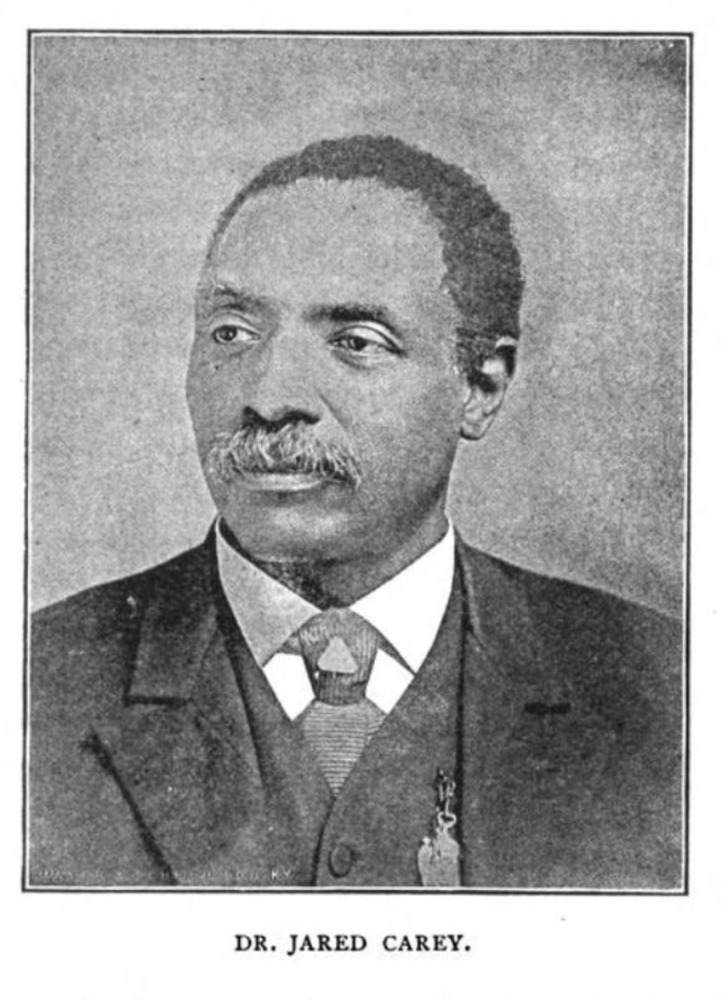

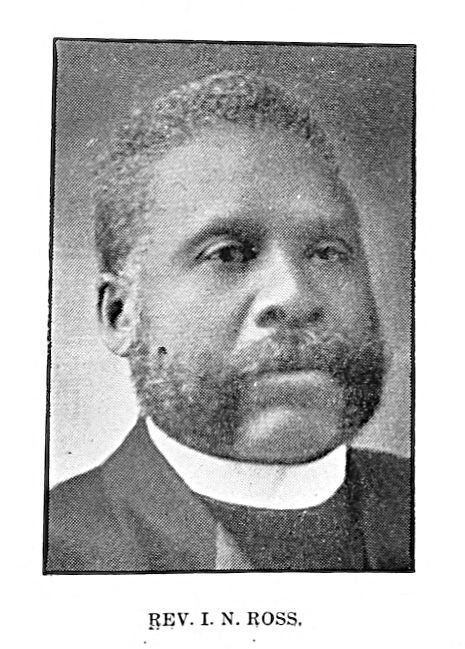

Many of those who sponsored the Coffin memorial were orphanage trustees, Republicans, and pastors, such as George Bundy, George Coble, Andrew DeHart, Charles Dorsey, J.E. Harper, Henry Harris, H. Darius Prowd, and George Wyatt, from African Methodist Episcopal (AME), Baptist, and Presbyterian churches. Additional trustees were Dr. Jared Carey (1826-1903) and the Rev. Isaac Nelson Ross (1855-1927). Carey was a chiropodist (podiatrist), a trustee of Eastern District schools, and an officer of a Black bank. Ross was pastor of Allen Temple and later became an AME Bishop; he delivered the invocation.

To raise money, these preeminent men and their wives (“lady managers” at the orphanage) hosted a nine-hour lawn fete in 1901, with speeches, various amusements, and grand exhibition drills by the Bell, DeHart, and Old Garrison Camps, and the Excelsior Company, the latter commanded by Charles Schooley, a dentist. Both a female orchestra and Johnston’s Orchestra provided music.

Politician Bill Copeland, who had been U.S. Grant’s messenger at Vicksburg and a member of the Ohio Legislature, served as M.C. Eva Irvin, of Union Baptist Church, unveiled the memorial, a classic cippus. Inscribed in capital, non-serifed letters are the Coffins’ exact death dates and ages with modest epitaphs, “a Christian philanthropist” and “her work well done,” followed by “noble benefactors aiding thousands to gain freedom, a tribute from the colored people of Cincinnati.” The other sides feature decorative floral and geometric motifs with two crossed vines of ivy, symbols of fidelity, friendship, and eternal life. The Coffins had been in unmarked graves; Quakers found headstones ostentatious. The marker’s simple, non-figurative design reflects the Coffins’ humility.

While the group did not accept funds from whites, they invited at least two white Quakers, including surgeon, Dr. William Judkins (the Coffins’ physician?), to participate in the dedication. Rev. Benjamin Frankland, superintendent of Cincinnati Union Bethel, the city’s oldest social service agency, gave the benediction.

This was not the first tribute that Cincinnati’s African American community made to notable whites. In 1885, Carey, DeHart, and others gathered in a church for a program in memory of Gen. Ulysses Grant (who promoted the 15th Amendment, although he had been a slaveholder). In 1896, the two men with Prowd, R.D.G. Troy, and others had a meeting at Union Baptist Church and planned a(n unrealized) monument to novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe.

By publicly memorializing whites who supported racial uplift, Cincinnati’s senior Black leaders demonstrated to themselves and white society their personal relationship with and ongoing remembrance of the Coffins, as well as their gratitude, generosity, Christian faith, civic-mindedness, political alliance, interracial cooperation, and shared American identity.

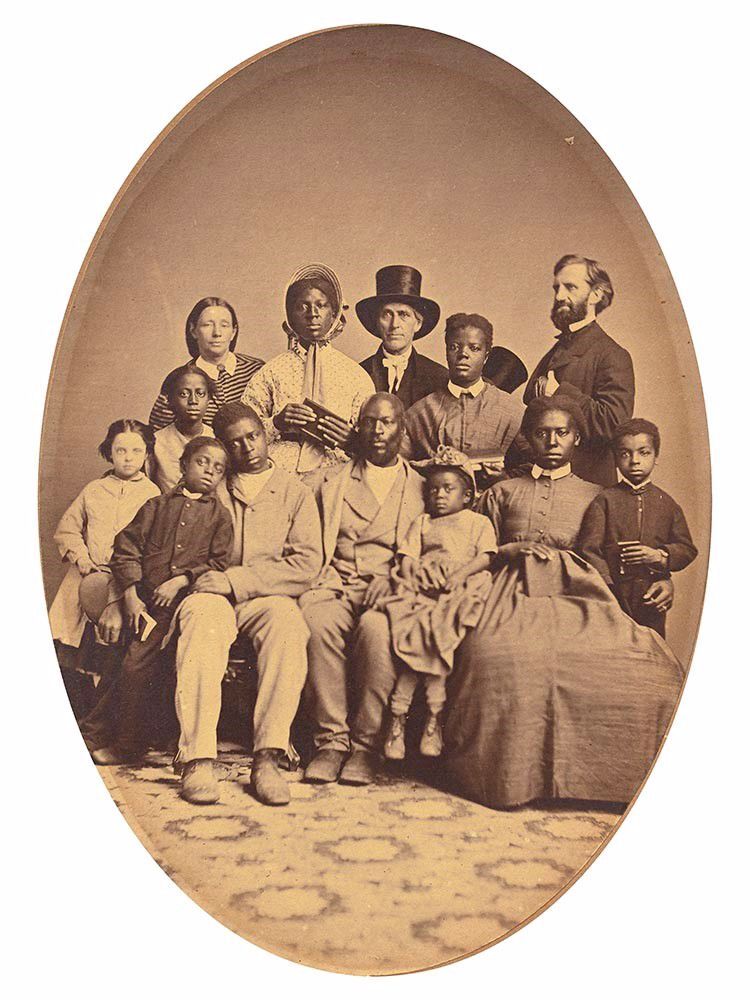

Images