Site of Frey’s Park

A short-lived, African American resort park near Coney Island

In the early 1900’s, Thomas A. Frey owned a picnic grove in the village of California, Ohio, near the Coney Island Amusement Park. Coney Island, at the time, was whites-only, but African Americans could gather on Frey’s property. Frey wanted to add a small concert pavilion. Local officials, however, opposed him bitterly.

Around 1902, Thomas Frey and his nephew William T. Frey, who were African American, began purchasing land on the north side of Renslar Avenue, near the California waterworks, just north of the Ohio River. The site was only a mile from what was originally called Parker’s Grove, the “Coney Island of the West.”

Thomas Frey initially laid out a baseball diamond on the property. Then in March 1910, he got a permit for construction of a two-story dwelling, with a public room on the ground floor where beer could be served. He also had a phone line installed. Frey’s picnic grove was in use that summer, when the Cincinnati Enquirer reported that “The outing given at Frey’s Park by the Republican Union was one of the most successful ever given by colored residents of this city.”

Frey hired architect Charles Fasse to design a single-story concert pavilion, sixteen feet wide by eighty feet long. The drawings were complete by September 1910. But, when Frey applied for a building permit, he was refused. Officials said they suspected that Frey might use the pavilion for dancing, which was forbidden inside California limits. (California was annexed by the City of Cincinnati in 1910 but retained some level of local control.)

Frey’s attorney pointed out that since the proposed structure complied with the building code, the authorities could not legally deny Frey a permit simply on the grounds that he might later use the structure for an illegal purpose. The Cincinnati Commercial Tribune reported on October 26,

“The long, drawn-out fight waged by Thomas Frey, who wished to secure a building permit for the erection of a concert hall in California, O., was ended yesterday when Building Commissioner Kuhlman issued a permit for a one-story frame shelter house… . The permit was not secured until Frey got a writ of mandamus compelling the commissioner to issue it.”

So Frey got his pavilion built and open. But dancing did occur there, and roller skating, too. Concerned citizens of California descended on the office of Cincinnati Mayor Louis Schwab. The Cincinnati Post reported,

“The delegation charged Frey was giving dances and permitting roller skating at his hall, although he did not have a license. Mayor Schwab declared that he would not, under any circumstances, grant a license to Frey. ‘It is my observation,’ the Mayor said, ‘that beer and dancing do not go well together, especially when an indiscriminate crowd is being served.’”

In June 1911, a patrolman named Fitzpatrick “swore out a warrant in Police Court Friday, charging Thomas Frey, of California, with conducting a public ballroom for negroes at California without a license.” Thomas Frey was arrested.

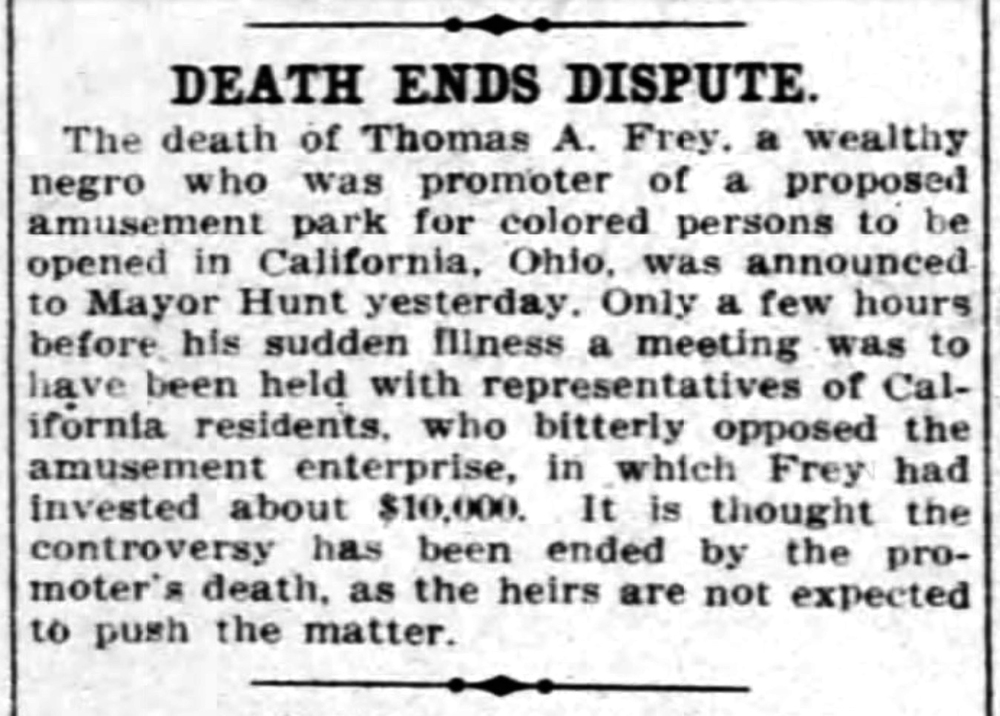

It isn’t clear what happened next, except that the conflict stretched into March 1912. And then Thomas Frey caught pneumonia and died. The Cincinnati Enquirer reported,

“The death of Thomas A. Frey, a wealthy negro was promoter of a proposed amusement park for colored persons to be opened in California, Ohio, was announced to Mayor Hunt yesterday. Only a few hours before his sudden illness a meeting was to have been held with representatives of California residents, who bitterly opposed the amusement enterprise, in which Frey had invested about $10,000. It is thought the controversy has been ended the promoter’s death, as the heirs are not expected to push the matter.”

Frey’s Park outlived its founder by a couple of years. The summer after Frey passed away, an African American baseball team, the Avon Oaks, secured the use of Frey’s Park as their regular home field. A labor union picnic was held there in the summer of 1914. After that, references to “Frey’s Park” disappear. And at that time, the racial integration of Coney Island was still more than 40 years in the future.

Images