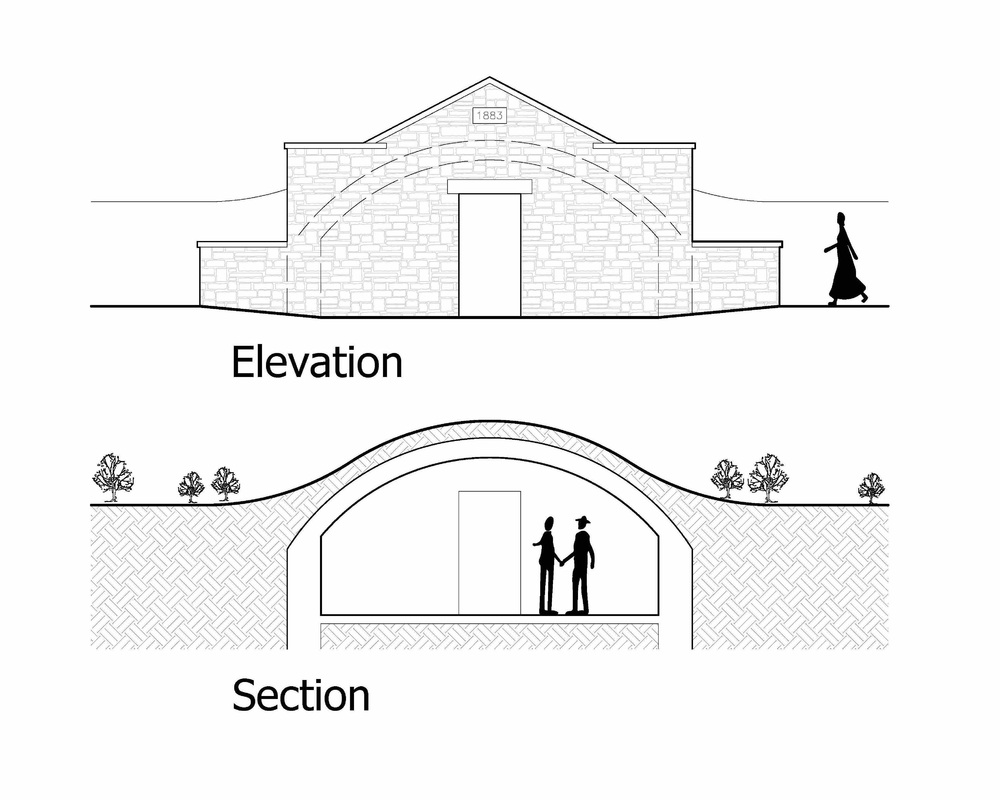

Receiving Vault, United American Cemetery

Site of attempted body-snatching in 1883

A central fact of 19th-century cemeteries was that if someone died in winter, when the ground was frozen too hard for a grave to be dug, the body would have to be stored someplace, possibly for months, until a thaw.

A cemetery of any size would have within its grounds a receiving vault, made of stone or brick, for the temporary storage of bodies. But there were, at the time, people who would try to steal bodies from cemeteries, to sell them to medical schools as subject for dissection. And a vault was always a weak spot in cemetery security, because it was, at least in principle, easier to steal a body from above ground than from below.

Body-snatching was a common crime, and one that was influenced by race and class. The medical schools that purchased cadavers for dissection were run by people who were white. The people filling this demand by digging up bodies were sometimes white and sometimes Black. The bodies being stolen were sometimes white and sometimes Black, but the problem was worse in cemeteries where most people were poor and politically powerless, which certainly included Black cemeteries.

United American Cemetery in Madisonville is a large, African American cemetery, dedicated in 1883, and it has an extant receiving vault. The vault has the date “1883” carved in a stone over the door. Inside, the vault is 20 feet wide and 25 feet deep. It is built into a hillside, to keep it cool.

During the 1880’s, a sexton lived full-time in a house on the property. The sexton’s job was to dig and fill graves, and to be on the lookout for body-snatchers.

In the winter of 1884, an African American man named Dangerfield Early died in Walnut Hills. He was pastor of the Walnut Hills Baptist Church. In 1858, he had started a school in his home, and this institution evolved into the Douglass School. But Reverend Early’s interment didn’t go easily. A newspaper account from December 13 says,

“Again the patrons of the new Colored American Cemetery are struck with consternation. A few days ago it was discovered that the key to the vault had been stolen and other mysterious maneuvers practiced thereabouts. Considerable apprehension was also felt that parties were trying to steal the body of the late Rev. Dangerfield Early, now enclosed in the vault; in fact such was the excitement that relatives of the deceased, well armed, stood guard upon the grounds out there for several nights.”

The importance of the vault goes beyond the role in played in the saga of body-snatching. The vault has been the temporary resting-place of many persons, known and unknown. And occasionally, the vault performed a more ceremonial function, as a place where mourners could gather to pay respects to the body of someone lying in state.

In 1915, a prominent African American minister named M. C. B. Mason died. He had been an officer in the Methodist Freedmen’s Aid Society, and his speaking tours crisscrossed the United States, Canada, and Europe. His family wanted him to be buried in Chicago. Still, Mason had lived for many years in Cincinnati, and it was important for his body to come to Cincinnati so that his many local friends could pay their respects. The Northwestern Christian Advocate reported, “The body was placed in a vault in the Colored American Cemetery in Cincinnati, where it will remain until the family secures a lot near Chicago.”

Images