West College Hill Neighborhood

Springfield Township Community Believed to Be Oldest Black Subdivision in Hamilton County

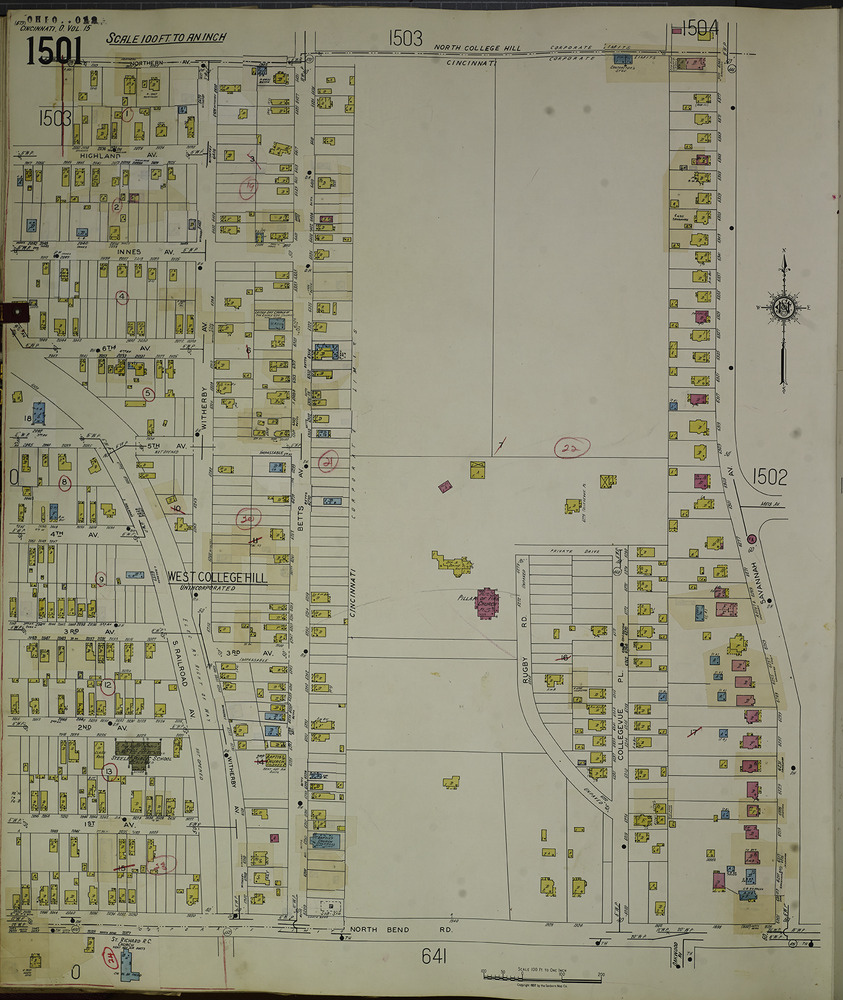

Sandwiched between the Cincinnati neighborhood of College Hill and the City of North College Hill, West College Hill is one of Springfield Township’s geographically detached neighborhoods. This unincorporated community is bounded by North Bend Rd., Betts Ave. and Northern Ave., with Eiler Ln. serving as its boundary with Golfway, another Springfield Township outlier. The small neighborhood is primarily residential, with minimal retail, several churches, a community/senior service center, and the 10-acre Crutchfield Park serving as amenities.

In 1888, a small group of Baptist settlers started meeting in the rented basement of the Belmont Flats on Hamilton Ave. in College Hill. Construction of their new church, St. Paul Baptist Church, started in 1890, on what is now Betts Ave. in West College Hill. The small frame building was nicknamed “The Little Wooden Church on the Hill.” This is now First Baptist Church, a congregation approximately as old as the neighborhood that surrounds it.

Charles M. Steele, the first mayor of Hartwell and a real estate investor with property in the West End and elsewhere, developed a subdivision here for African American residents and sold the first lots in 1891. In 1907, he opened an adjacent Black-only subdivision. West College Hill is believed to be the oldest Black subdivision in Hamilton County, and retains a sizable Black population today.

It is believed that Melvina and Charles Middleton purchased the first lot in the Steele subdivision, building a small shotgun house for their family. Soon after, Melvina’s sister and her husband purchased two adjacent lots for $100, as part of a commonly seen pattern of extended Black families clustering in close proximity. By 1910, 150 families, or approximately 430 residents, lived in West College Hill.

Some families purchased the small, inexpensive lots outright, others with a down payment followed by monthly installments. Most families built their homes themselves, or with the help of relatives or friends, though some used contractors or carpenters. Often, residents built their wood-frame houses room by room as they were able to acquire building materials, including salvaged lumber.

According to Henry Louis Taylor, Jr. in his chapter “City Building, Public Policy,” in the book Race and the City: Work, Community, and Protest in Cincinnati, 1820-1970, by the 1920s, there was a robust informal market consisting of “real estate speculators, building material companies, banks, savings and loan companies, builders, and an army of carpenters all willing to help low-income workers build their own houses.”

In 1925, Cincinnati became the first city in the US to have a comprehensive plan approved by its City Council. The Official Plan of the City of Cincinnati mentioned several problems with previously subdivided plats, including lots being too narrow or shallow “for fire protection, privacy, sunlight and space for gardening or play.” Though this criticism didn’t name West College Hill or similar communities, it doubtless applied to the small plats of this subdivision. According to the Plan, lots should be at minimum 50 feet wide, “except that in the subdivisions laid out for wage earners a minimum width of 40 feet can be allowed, provided that a minimum of 16 feet between houses shall be insisted upon.”

Many of the lots in West College Hill are only 25 feet wide. Contrary to the Plan’s assessment, residents kept livestock and tended to their own vegetable gardens. Water came from wells or cisterns. Coal and wood were typically used for heating and cooking, making the wood-frame homes vulnerable to fire, particularly during the winter.

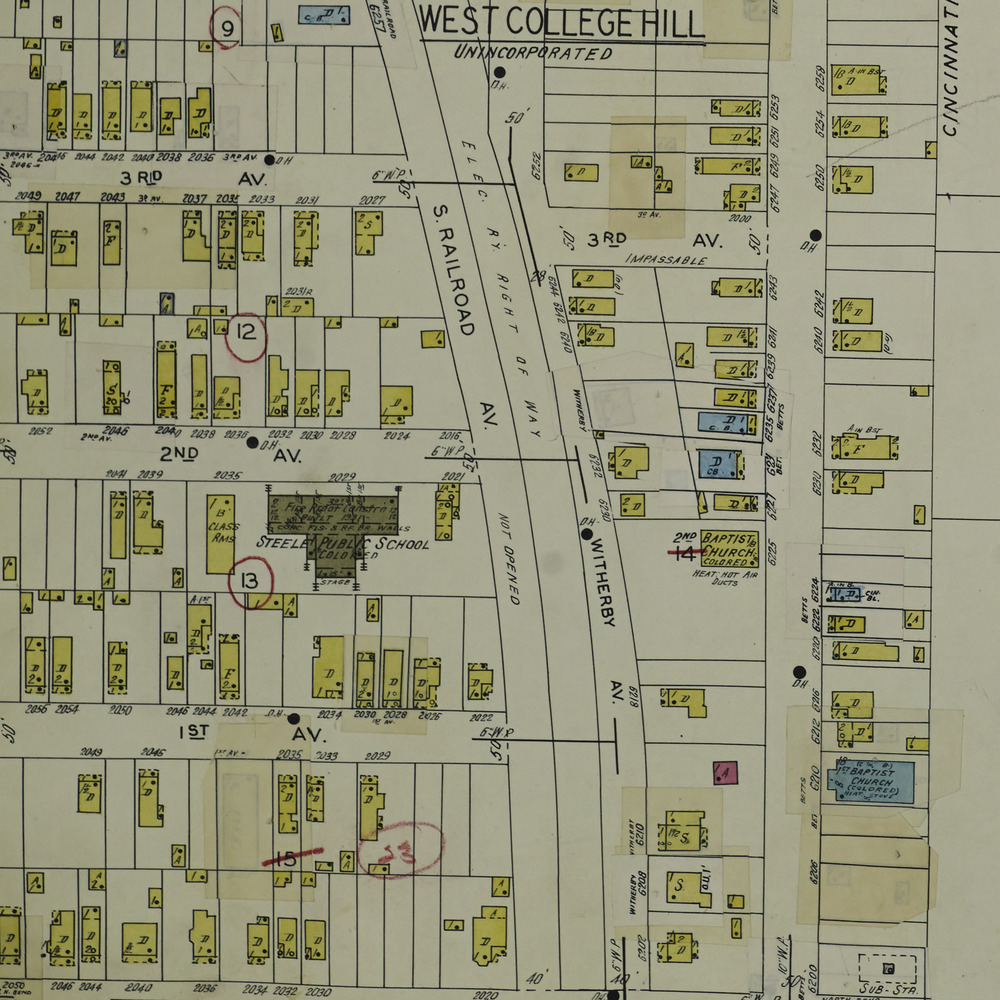

The first school in West College Hill, a one-room schoolhouse, had been built in 1904. Although the community had no formal governmental structure of its own, a group of resident volunteers organized to respond to fires and medical needs. By the 1920s, in addition to its own school, the community had four churches and a constable appointed by Springfield Township.

As there were virtually no land use regulations in Hamilton County, some of the rapidly developing Black-populated suburbs lacked paved roads, sewage, water, and electricity. The homes were modest and sometimes located on poorly developed lots. Home values in West College Hill were low, averaging $350-500, but the homeownership rate in the community was high at 60%.

In a shockingly disingenuous statement, writers of the 1925 City Plan claimed that, “The colored population is continuing to increase fairly rapidly, while the number of houses in which they may live is remaining stationary.” Of course, some local Black residents were taking matters into their own hands on the outskirts of the city.

In the Better Housing League report of 1928, Bleecker Marquette said, “We find developing just outside the corporation lines potential slums which will eventually contain all of the bad conditions we are fighting against now.” BHL’s Standish Meacham called them “bad spots,” while Clifford M. Stegner, Cincinnati’s director of buildings, used the term a “menace to the city.”

By 1930, 67% of Cincinnati’s Black population, more than 30,000 residents, lived in the West End. Most were tenants, and they rented much of the cheapest housing available. Black residents owned just under 2.5% of Cincinnati’s 45,085 owner-occupied dwelling units, and their homes had some of the lowest property values in the city.

The median value of Black owner-occupied housing in 1930 was just under $4,500. That same year, Music Hall hosted its annual Home Beautiful Exposition, featuring a model home designed by Wilbur M. Firth. “For 1930, the dwelling designed for the show was to cost no more than $10,000. Event managers believed the average person should be able to afford this home.” (In fact, the median value of a single-family home in Cincinnati owned by US-born whites was just over $8,000 in 1930.)

At the same time, echoing the Official Plan of the City of Cincinnati, the Better Housing League advocated for a kind of trickle-down theory of housing affordability, believing that Black residents, with their typically lower wages and barriers to professional advancement, could not afford the cost of new home construction. Therefore the BHL encouraged higher-income white residents to move out of Cincinnati’s basin, including the West End, thus making their older homes available to Blacks.

Meanwhile, however, homeownership was relatively high in the primarily Black-populated suburban subdivisions of West College Hill, Kennedy Heights, Wyoming, Lincoln Heights, Woodlawn, and Hazelwood.

In 1931, the original one-room school in the community was replaced by Steele Grade School, serving the area until 1965.

By 1940, 77% of West College Hill residents were homeowners. Most West College Hill residents worked outside the neighborhood, but the community also contained several Black-owned businesses, including grocery stores.

By 1947 Steele Grade School, staffed by Black teachers, had 230 students, all Black, while the population of West College Hill was approximately 1,300.

Josie Becker Elementary School in North College Hill opened in 1962 partly as a replacement for Steele.

In 1966, the neighborhood was home to 285 families. That year, in an address before the Associated Church Press, Sargent Shriver quoted the Reverend Edward Jones, the longtime Pastor of the First Baptist Church in West College Hill, “The scruffy houses were only a cut above shacks–no windows, no heat, no air, no nothing.” Shriver recounted Jones’ description of the community coming together to improve its immediate environment by covering up a garbage dump and tearing down condemned houses.

The 1970 US Census offers an informative snapshot of West College Hill and surrounding communities. The neighborhood was 95.5% Black, compared to 11.2% in College Hill and .4% in North College Hill. The city’s Black population was 27.6% at the time. Mean family income in West College Hill was $6,749, $13,030 in College Hill and $11,446 in North College Hill. The city’s mean was $10,435. In 1970, 24% of West College Hill families lived below poverty level, over 5% more than the city’s poverty rate.

In describing West College Hill’s housing stock in 2010 and 2016, the Springfield Township Comprehensive Neighborhood Master Plan states that it is “an area in transition due to the antiquated nature of the residential structures and the lack of maintenance and private investment of property owners.”

This same plan calls for developing a “detailed plan and cooperation agreement with Habitat for Humanity to provide new housing development within West College Hill.” Indeed, the organization has done work in the neighborhood in recent years and owns some residential property.

Images