Gravesite of Louis Kelly

Cemetery sexton who fought against body-snatchers

On November 1, 1879, Louis Kelly was appointed sexton of Union Baptist Cemetery. One evening a few weeks later, a woman knocked at the sexton’s cottage and asked Kelly “if he did not want to earn a few dollars.” Kelly said yes, if it could be done honestly. The woman laughed.

The woman told Kelly that what she had in mind was “as fair a method of earning a livelihood as a great many others.” She threw back a heavy veil, “disclosing rather prepossessing features,” and explained that she was a resurrectionist, or body-snatcher, someone who steals corpses to sell to medical schools as subjects for dissection.

The woman told Kelly that he could have ten dollars for each body he would supply to her; or he could simply stay indoors while her partner did the work, and have half the sum. Kelly refused the woman’s offers, and she left.

On December 17, Kelly had another caller, this time a man. The man said that “All the sextons were making money in this way, and there was no reason why [Kelly] should be the exception.” The visitor then said that a 15-year-old girl named Maria Burnside had died recently, and that her body was scheduled to be brought to the cemetery the following day. The visitor suggested that “her body would be a good one to commence on.” Kelly ordered the man away.

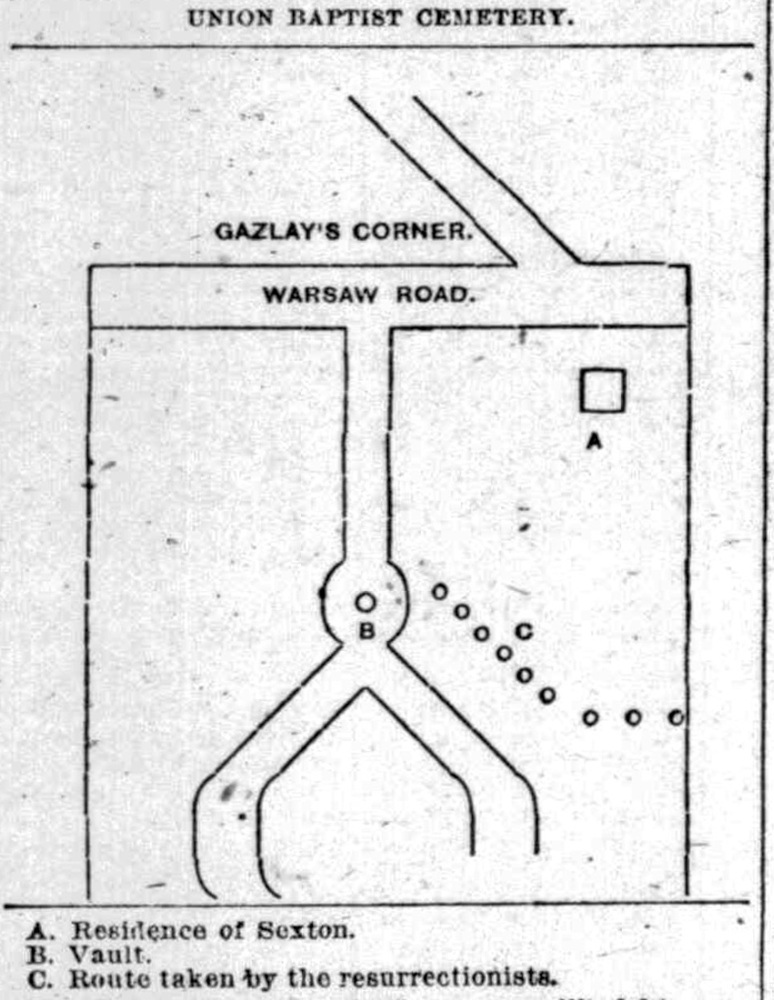

The body of Maria Burnside did indeed arrive the following day. Since the ground was frozen too hard for a grave to be dug, the coffin was stored in the cemetery’s receiving vault. (The vault was in the center of the cemetery, where the white building is now.) Kelly added two more locks to the door of the vault, and he induced half a dozen neighbors to patrol the cemetery with him that night.

Around 11:00 pm, one of them saw a light flickering near the vault. Kelly and his associates drew their guns, rushed toward the vault, and fired. One or more persons returned fire. Eighteen shots were fired, but no one was caught or killed.

Five days later, on December 23, a bad storm came up, with driving rain, thunder, and lightning. Sexton Kelly stood watch until midnight, when the rain drove him and the dogs indoors. The next morning, Kelly discovered that the door to the vault had been wrenched open with a crowbar. Of the four coffins inside, three were now empty.

The body of Maria Burnside was missing. So were the bodies of two adult men. The only body not taken was that of an 18-month-old child, apparently less desirable as a subject for dissection. Trustees of Union Baptist Church, along with Maria Burnsides’ mother, visited the local medical colleges but could not find the bodies.

This experience only heightened Louis Kelly’s resolve. Four years later, in March, 1884, a reporter from the Cincinnati Post visited Union Baptist Cemetery. Louis Kelly said this:

“They never got a body from my cemetery but on one occasion since I took charge, and then they got three. But I’ll bet they will not try it on me again. … I don’t think they want to make my acquaintance, for I’ll shoot to kill the first man I find in the graveyard.”

The reporter asked Kelly whether any of the coffins temporarily stored in the vault ever turned up empty when the time came for burial. Kelly said, “No, sir, and I open every one in the presence of relatives before lowering them, and if anyone thinks his dead is not safe, let him come to me and pay the cost, and I’ll stake my reputation on finding them undisturbed.”

Kelly remained sexton at the cemetery until 1891, when a scandal erupted: it was alleged that Kelly had buried bodies without a permit and had pocketed the money, depriving the church of their share of the burial fees.

When questioned, Kelly readily admitted that he had buried many bodies without permits. But he insisted he had done so only when it was demanded of him by one, particular undertaker: William Porter. William Porter was the only Black undertaker in Cincinnati, and he was a Trustee of Union Baptist Church. Kelly said that he “dared not disobey” Porter, who had made it clear that Kelly’s job was at stake. Kelly also said that the financial advantage went to Porter, not to himself.

In the end, Louis Kelly was fired, and William Porter lost his position as church trustee.

Louis Kelly died in 1907 and was buried in the cemetery he had worked so hard to protect. His tombstone calls him the “First Superintendent of Union Baptist Cemetery.” While there had been several earlier sextons, Louis Kelly’s vigilance and long tenure make him a major figure in the history of this cemetery.

Images