Wilda Gunn

Commercial Artist of Cincinnati and Cleveland

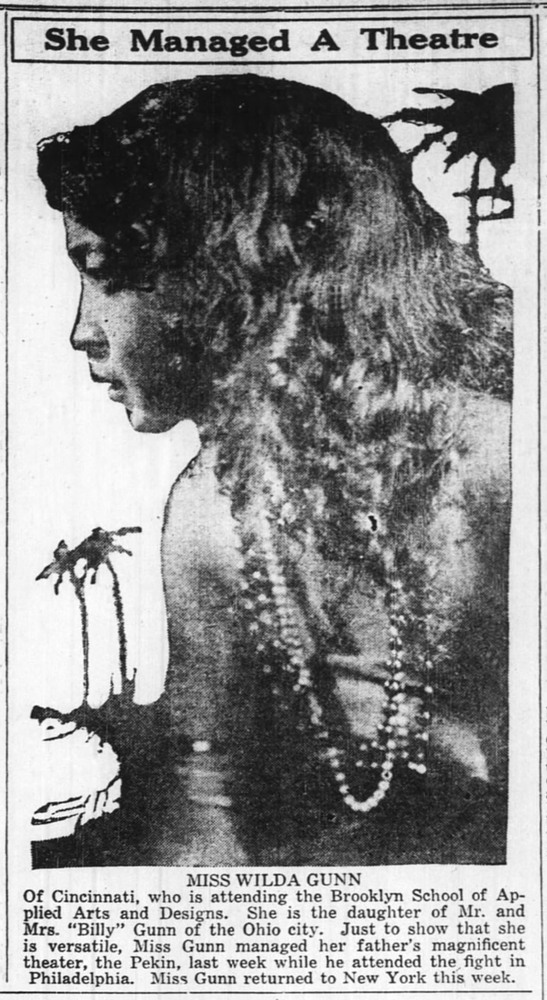

Wilda Gunn was a commercial artist, costume designer, and muralist. Born in 1905, she grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio, where her father managed an African American movie house, the Pekin Theater. In 1923, she moved away to study art and design at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York.

In New York, Wilda Gunn befriended a slightly younger woman named Blanche Dunn. Wilda Gunn began advising the younger woman on clothing and style. Blanche Dunn became a fashion icon of the Harlem Renaissance. Today, Wilda Gunn is remembered largely as a mentor to Blanche Dunn.

By 1930, Wilda Gunn had returned to Cincinnati. In 1932, she designed costumes and scenery for the Cincinnati Civic Opera, an African American opera company. In 1934, Gunn opened a design studio (known simply as "The Studio") in the Supreme Life Insurance building at 612 W. Ninth Street. There, she offered “artistic designing, fashionable habiliments, [and] costuming deluxe.”

Around 1943, Gunn moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where she opened her studio at 2587 E. 55th Street. She was married to a Mr. Norman Chandler but quickly divorced. In the aftermath of World War II, Gunn worked with military veterans who had injured their hands or arms, teaching them how to use art and art techniques as a form of occupational therapy.

In 1944, Wilda Gunn painted floral murals for Handy's Paradise Bar at 4410 Woodland Avenue in Cleveland.

A few years later, Gunn was asked to submit a proposal for another mural, this time in the bar of the Hotel Majestic. Gunn submitted a sketch of conventional design, showing “an easy and ancient scene of a small town railroad station, with attendant passengers waiting for train in the distance, horse and buggy crossing the tracks, family group waiting for the train… .”

Gunn got the contract for the mural. Then she painted something quite different. In June 1947, the Cleveland Call and Post reported that “this modernistic thing” that Gunn had “done free style, with an amazing flourish of beauty and confusion, caused many eyes to pop in wonderment… .”

A major figure in the mural was a mermaid with snakes instead of hair, representing, the reporter surmised, temptation. In one hand, the mermaid held a pair of dice. The other hand grasped the reins to a seahorse with a number 7 on its front, apparently to symbolize horse-racing.

The reporter continued their interpretation:

“Woman's body here is presented as the gateway to luscious pleasures and delights in the garden Eden, which must mean evil, for the entrance to this realm of delight is lightly covered with a huge web in the center of which a great black spider sprawls, ready to catch the flitting butterfly hovering near… .” The reporter described the spiderweb as a place “of lurid, sensuous, sexual delight.”

Other mural figures included a devil, a serpent, and “Another gorgeous, voluptuous creature, lost in the stupor and drunkenness of depravity and indulgence.” This side of the mural showed flowers “entwined in the serpent's grasp” that seemed “hopelessly emmeshed in the sweet aroma of evil.”

Alas, no originals or photographs of Wilda Gunn’s murals, or any of her other work, have come to light, at least not yet.

By 1951, in addition to her commercial art business, Gunn was owner-editor of a small magazine called the Cleveland Key.

Wilda Gunn died in Cleveland in 1952. She was 46. Her body was shipped home to Cincinnati. She was buried in United American Cemetery, where her parents and grandmother are also buried.

Images