Escape of the 28 in Cincinnati

The story of an undercover operation at Wesleyan Cemetery that led to the escape of 28 enslaved men, women, and children along Hamilton Avenue's road to freedom.

“The Company of Twenty-Eight Fugitives” was one of the most impressive Underground Railroad flights to Black freedom ever documented.

On the Road to Freedom

It started in Petersburg, in Boone Co., Kentucky. John Fairfield, a white man, and a slave rescuer for hire, engaged in the subterfuge of buying poultry for market for several weeks in an area of the county. Being white and in Kentucky, he was assumed to be pro-slavery and initially the slaves believed that also.

When they learned he was their friend, they paid him for his help with the little money they had accumulated from making baskets, selling their produce and eggs or what they were allowed to keep when they were “hired out.” On a rainy Saturday night April 2, 1853, a group of twenty-eight, most from the same community with many fleeing from the Parker and Terrill families, ran away hoping their absence would not be discovered until church time later on Sunday morning. They must have walked north along the ridge to Taylor’s Creek and then followed the creek to a place on the Kentucky shore, across from Lawrenceburg, Indiana where they met John Fairfield.

Crossing into Cincinnati

The band followed the bank of the Ohio River from Indiana into Cincinnati. They met John Fairfield near the three skiffs that would take then across the fast moving Ohio River. The delay of waiting for passengers of the sunken skiff cost them precious time and when daylight came they could not enter Cincinnati, for their wet and muddy appearance would give them away. The swiftness of the current and rain swollen river contributed to the failure of one of the skiffs. Fairfield hid them hungry and cold in the overgrown wet ravines below the mouth of the Mill Creek, while he went into Cincinnati to request aid.

Fairfield went to a friend of his, John Hatfield, a black barber and steamboat steward, whose home was on 5th Street between Race and Elm. A deacon of the Zion Baptist church, Hatfield was the leader of Cincinnati’s Vigilance Committee that watched out for the rights of free blacks and with his wife Francis and daughter Sarah, assisted many fleeing slavery. Hatfield sent for their mutual Quaker friend, Levi Coffin, and the Vigilance Committee. They all came quickly; as such a large group of fugitives would be in danger of discovery.

The Plan

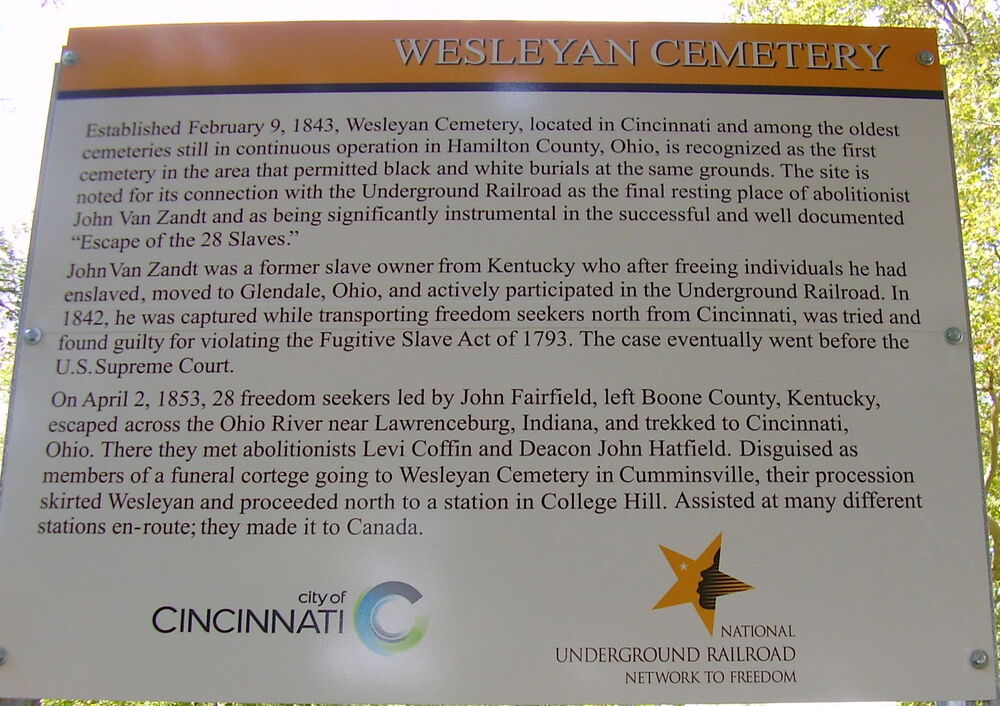

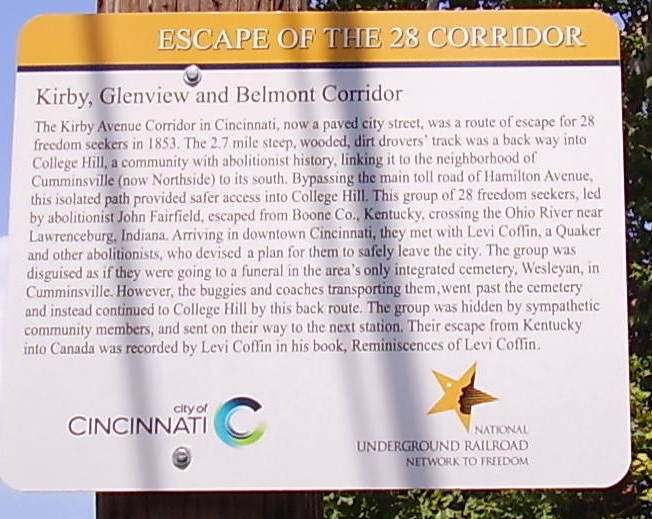

Together with Fairfield, Hatfield and Coffin formed a plan - two coaches would be hired from a specific German stable in the city while the fugitives were taken from their hiding places in buggies. A procession was to be formed with the buggies and coaches, as if going to a funeral, and slowly move along the road towards Wesleyan Cemetery in Cumminsville, the first integrated cemetery in the Greater Cincinnati area. Once there, they were to skirt the edge of the cemetery and take Colerain Pike until they reached the road going up into College Hill. There, they would find both Black and white abolitionist families to hide and shelter them. This included the Witherby’s, Cary’s, Farmers’ College and Dr. Bishop.

Rev. Jonathan Cable, a Free Presbyterian minister, abolitionist and “stockholder” in the Underground Railroad, who lived near Farmers’ College would make the arrangements in College Hill. Hatfield’s buggy was to depart from the funeral procession in Cumminsville and go straight to Cable’s house to notify him that a group was coming.

The Journey

While the coaches and buggies were being procured and volunteers assembled, Hatfield’s family and neighbors put together hot coffee and food to be taken directly to the fugitives, as they were hungry and cold. Blankets, too, were taken and while they ate, the plan was explained to them. One woman had an infant that was crying and suffering much from the cold and rain. She wrapped the baby tightly to her with a blanket. The women rode in the carriages, which were closed, and the men walked along side.

All proceeded as planned with the cortege. The buggies and coaches made it safely up the muddy College Hill road, “but, sad to relate, it was a funeral procession not only in appearance, but in reality” for when they arrived at College Hill, the suffering baby had died and would be buried in a College Hill cemetery the next day.

In the meantime, the “noble ladies of College Hill” had gotten together with Rev. Cable and decided what clothing and shoes would be necessary. Some travelers had lost their shoes in the mud and many were underdressed for the weather and this long journey. Their thin clothes were already ripped from going through woods and hiding in the overgrown ravines. The anti-slavery families of College Hill donated whatever additional clothing was needed.

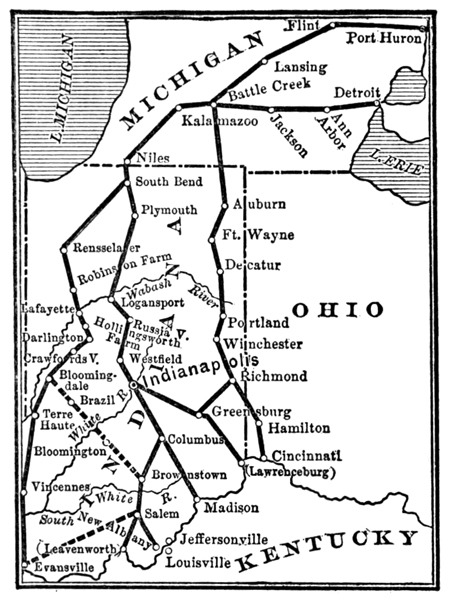

Rev. Cable and the families of College Hill hid the fugitives as preparations were made. Their number once again was twenty-eight as another fugitive had arrived during the night and joined their company. Their route was decided--first they would go through Hamilton to West Elkton and then through Eaton and Paris to Newport (Fountain City), Indiana where Coffin had previously lived.

As evening approached, they assembled in the house of the black Farmers’ College caretaker where Rev. Dr. Robert Bishop read a psalm and then this large group set off on their journey in three covered wagons each drawn by two horses. In pursuit were three men, slave catchers, from Boone County. The slaveholders offered a reward of $9,000 for capturing the group and $1,000 for a lead on their location. They offered this much since one of the fugitives was said to have been purchased for $1,200 just eight months before, one was Washington Parker, a favorite with his master, and another was a Baptist preacher, who surely knew how to read.

Towards Freedom in Canada

They moved through Indiana and into Michigan, where they spent the night in Coldwater among Wesleyan Methodists, rather than with the usual Quakers. They raised money and paid a white man, Fairfield, to lead them. This was an escorted escape where other people made sure the group were fed, housed and transported to their destination.He was with them every step of the way to Canada. He swore to protect them but also saw that they were armed to protect themselves. He oversaw the whole trip which had people of various ages and medical conditions.

Fairfield telegraphed Windsor that they were ready to cross. As they were loaded on forty sailboats and pushed off from the banks of the Detroit River. At 8 a.m., April 19, 1853 when the ferry boats started for the day, the station keepers crossed the Detroit River and joined the celebration. Henry Bibb, a former slave who escaped to Canada and founded the first black Canadian newspaper, The Voice of the Fugitive, witnessed their arrival and wrote about it in his paper.

------

Check out the Urban Roots podcast's "Cincinnati History is Black History" episode on Apple, Spotify, or YouTube to hear Kathy Dahl from the Hamilton Avenue Road to Freedom project tell this captivating story via audio!

Images