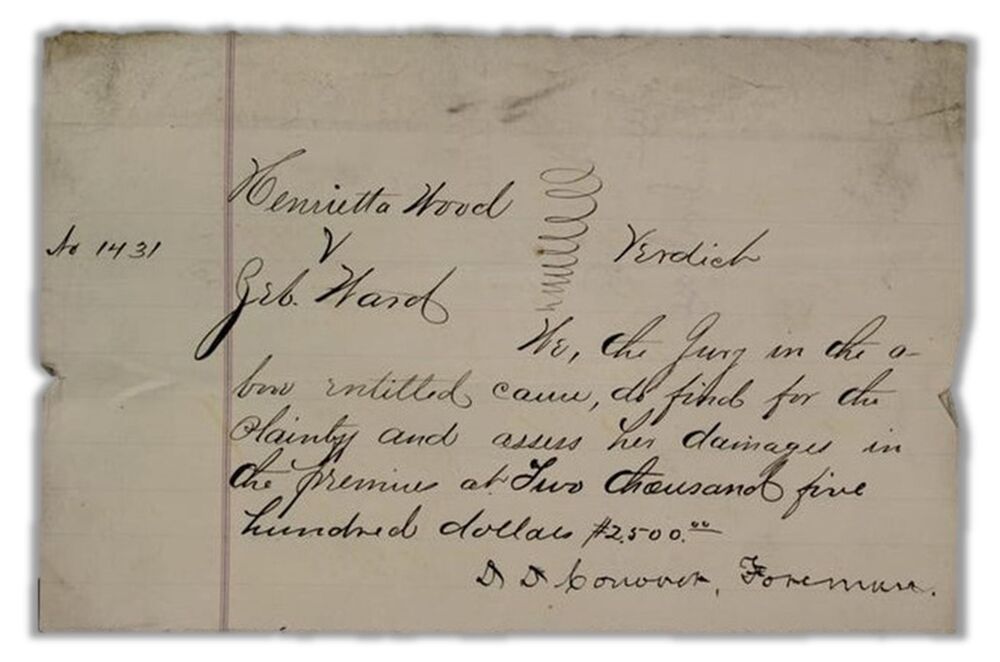

Henrietta Wood

Won the Largest Verdict Ever Awarded for Slavery Reparations in US History

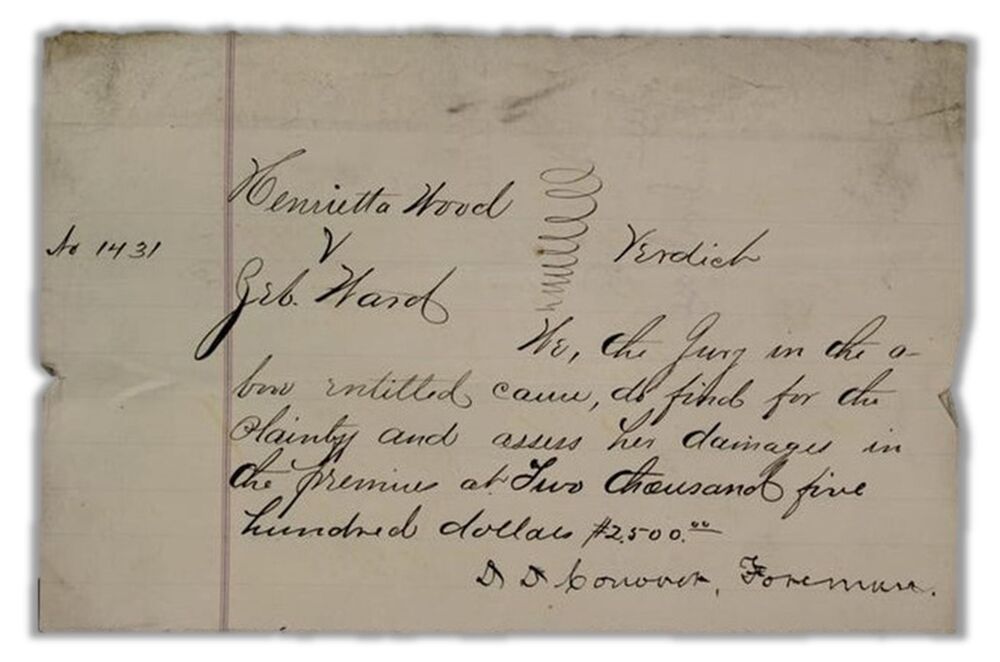

The life story of Henrietta Wood attests not only to her resilience, but also to the dangers people of color, both enslaved and free, faced during slavery. Henrietta Wood was born as a slave, but even after she was freed, she was kidnapped by three men with the help of her employer and sold back into slavery until the end of the Civil War. Her story, marked by tragedy, ended with victory, if not justice. In 1869, she filed a suit against one of her enslavers and was awarded a sum of $2,500.

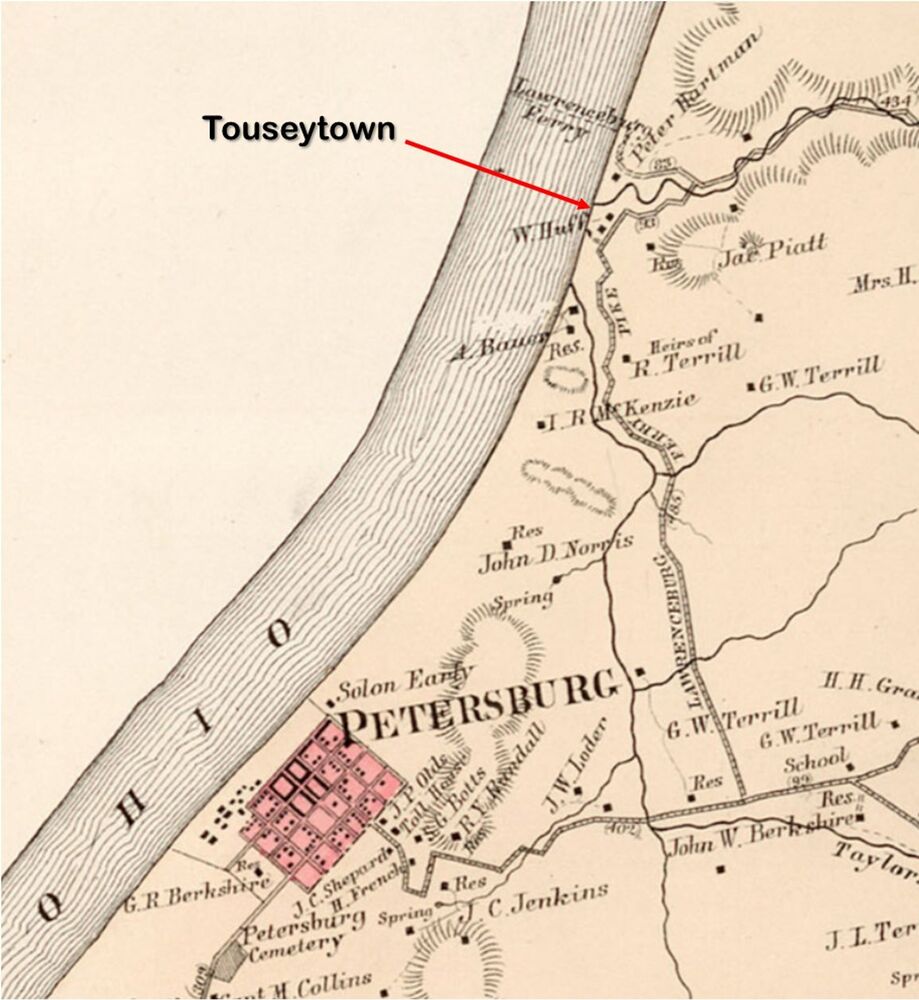

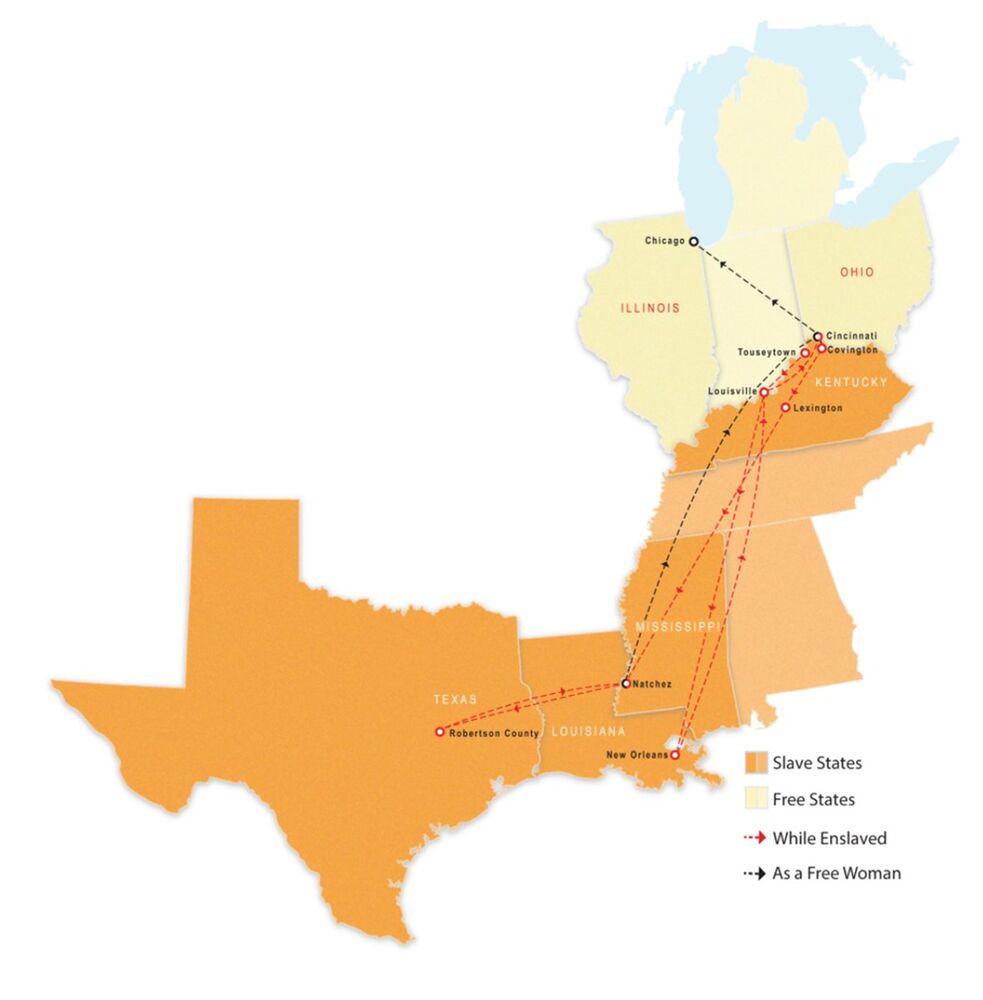

Henrietta Wood was born on the border of slavery, near the Ohio River which divided the North and South, sometime between 1818-1820. Her early years were spent in Touseytown, a small river settlement in Boone County, Kentucky (shown on the map below). The town was named for Moses Tousey, who held Henrietta and her family in bondage.

When Tousey died in 1834, Henrietta was separated from all she had known when sold to a Louisville merchant for $700. This sale soon led to another and Henrietta found herself on a riverboat headed to Louisiana as the property of a Frenchman named William Cirode.

For the next several years, Henrietta remained enslaved in New Orleans until financial problems caused the breakup of the Cirode family. Around 1845, William Cirode left for France and his wife, Jane, returned to Louisville, taking Henrietta with her; they stayed for several years.

In 1848, Jane Cirode decided they should move to Cincinnati, where she planned to open a boarding house. Because Ohio was a Free State, Henrietta could not stay indefinitely with Jane as an enslaved person, but Jane wanted her help in the boarding house venture. She made the decision to grant Henrietta her freedom.

Ohio's Black Laws required registration (along with proof of freedom) in order for free African Americans to be legally employed in the state. Jane and Henrietta went to file papers of manumission, in the Hamilton County Courthouse; proof that Henrietta was no longer enslaved.

Once Jane's business was up and running, Henrietta worked for her and other business owners in the area. Her newfound status was not enough to ensure pay equal to that of white laborers, but she still had agency over her own life. From 1848 to 1853 Henrietta enjoyed what she later described as a “sweet taste of liberty.” Sadly, her newfound freedom was not to last.

Enslaved people represented wealth to slaveholders and the Cirode children felt Henrietta's manumission had cheated them out of their inheritance. They were the force behind a deceitful plot to reclaim some of that inheritance by illegal means. They devised a plan to hire someone to kidnap and sell a free woman.

In 1853, the plan was put into motion. Rebecca Boyd, who owned a boarding house where Henrietta sometimes worked, asked her employee to accompany Boyd on an errand. Together, the women crossed the Ohio River by carriage. Once they reached Covington, KY, Henrietta was delivered to a waiting gang of kidnappers, led by Zebulon Ward, a deputy sheriff with little respect for the law.

The kidnappers had planned well, they had already located and stolen Henrietta's free papers, which was the only way for her to prove she was legally a free woman. She was now on Kentucky soil and Henrietta's prospects for regaining her freedom rapidly diminished. Her word alone would not do; Henrietta needed to find help.

The group travelled several miles south toward the small town of Florence, in Boone County. Ironically, the briefly free woman had been forcibly returned to the place where her life of enslavement had begun.

Because her kidnappers had other nefarious tasks to attend to, they stopped at a hotel on the Lexington-Covington road in Florence and locked Henrietta in a room there until they could return and continue their journey. The innkeeper was not unfamiliar with Ward and his gang, but this was an unusual request, even for slave-traders. Henrietta may have sensed that she would find a sympathetic ear, so she told the innkeeper that she had been kidnapped and was a free woman.

She must have been convincing, because the man did his level best to help her, even travelling to Lexington, where Henrietta was next taken.

Even with the help of the innkeeper, Henrietta's freedom was denied, all the way to the Kentucky Court of Appeals. The confiscated freedom papers were the only solid “proof” of her status as a free person. Ward claimed her as a slave and the courts returned her to his custody. For the next seven months, Henrietta was held as a slave by the Ward family. During her time with them, she had been defiant with Ward's wife and was taken for punishment. She challenged Ward himself on the matter, and he backed down. At the time, it seemed the point was scored by Henrietta, but Ward had other plans in mind.

It was now 1855, nearly two years after her kidnapping. Since Ward had escaped the consequences of his crime, he was free to sell Henrietta to whomever he pleased. He decided to sell Henrietta to notorious slave-trader William Pullum. Pullum's firm trafficked enslaved people by the thousands from the upper South to “Forks in the Road,” a large slave market in Natchez, Mississippi. Being “sold South” was a threat used regularly by Kentucky slaveholders, seen as a fate worse than most. Henrietta would have little hope of finding help or freedom there.

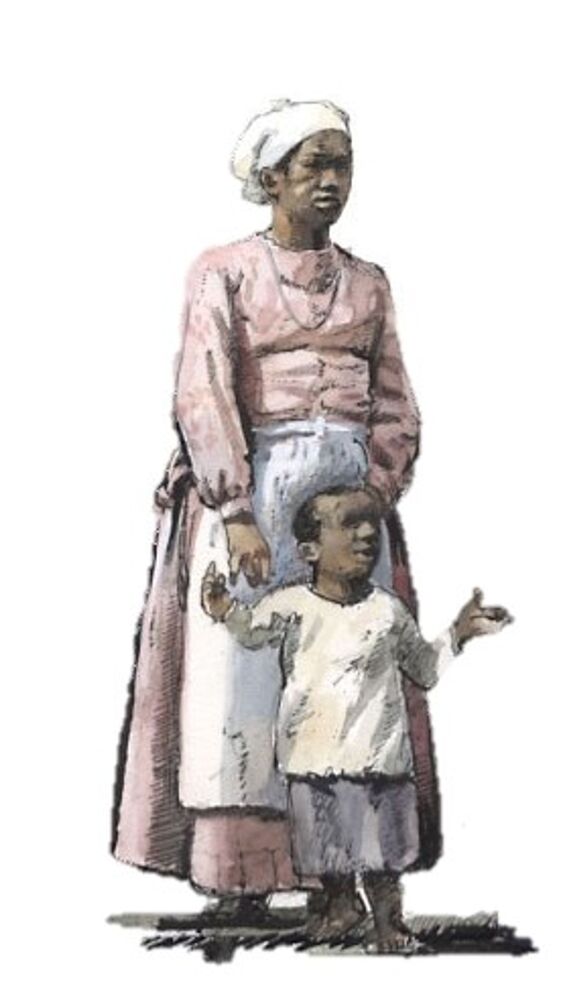

She was placed on the auction block and found herself in the clutches of Gerard Brandon of Washington, Mississippi. Her future looked bleak, but a small miracle was on the way. Henrietta's son Arthur Simms came into the world soon after her arrival at one of the South's largest cotton plantations, Brandon Hall. It's unclear who Arthur's father was, but it seems she may have been pregnant during her trip south. Once on the large plantation, the new mother was introduced to the harsh work and violent existence of enslaved people in the Deep South. As always, Henrietta was resilient. With her son by her side, she survived the fields and was later moved to work in the house.

After the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, many slaveholders moved west, hoping to retain ownership of the people they held in bondage. The Brandon family took this path, relocating to Texas. Henrietta and her son Arthur were among the enslaved people they took with them. It's possible that Henrietta had no knowledge of the Emancipation Proclamation. This fact was successfully kept secret by some slaveholders for years. Even those who were aware may have felt helpless, left with little to no resources in a country deep in the throes of war.

After the end of the war, steady employment was hard to find; working for a former slaveholder was sometimes the only choice. When the Brandons returned to Mississippi, Henrietta and her son came along, staying on for several more years.

At long last, in 1870, Henrietta and her son moved to Cincinnati, the place she had first known freedom. It was there that she began the process of seeking reparations for the years of freedom stolen from her.

She brought suit against her captors with the help of Covington lawyer Harvey Myers, who was also her employer. Myers was a man of means but his political views were not the norm in his neighborhood, where slavery was very recently accepted. Around the time Henrietta began to work for him, Myers was among several Kentucky attorneys calling for change in Kentucky law that disallowed testimony of African Americans in court. With his help, Henrietta began to build her case.

In 1878, after overcoming many legal hurdles, Henrietta was ultimately awarded the sum of twenty-five hundred dollars, for lost wages and damages. Though she had sued for a much higher amount, this was no small settlement. For context, in 1878, Henrietta could buy a pound of bacon from her Cincinnati butcher for about 9.5 cents and rent a large apartment in town for $10 per month. Henrietta had won the battle, but the years stolen from her were never acknowledged by her captors.

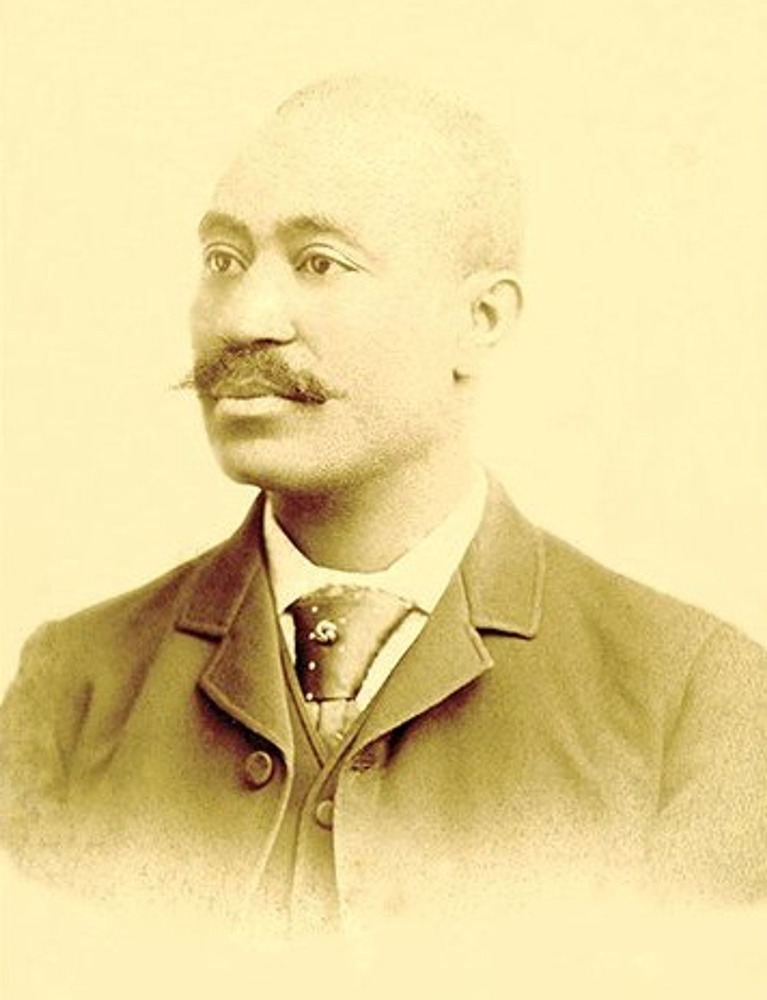

Sometime before 1880, Henrietta and Arthur left Cincinnati and began life anew in Chicago. The money awarded Henrietta allowed them to settle without the struggles they had previously suffered. Arthur purchased a home outright in 1885, likely with part of Henrietta's winnings. This home became a foundation of wealth for the family. Records show the home's equity was mortgaged by Arthur for tuition in pursuit of a law degree.

The boy who had been at his mother's side in the Cincinnati courtroom had found his chosen profession. In 1889, Arthur Simms became one of the first African American graduates of Union Law School (now a part of Northwestern University.)

Henrietta lived for over thirty years in Chicago, enjoying the success of her son and his growing family. In 1912, she died at the age of 94, having lived to attend the wedding of her granddaughter.

Henrietta left more to her descendants than the financial boost from the lawsuit. A more precious gift was the example of her unrelenting fight for justice; a show of strength and confidence for the generations who followed her. Among her descendants are musicians, professionals, academics and even a Tuskegee Airman. Her legacy is one of resilience.

Images